Ayat Mneina

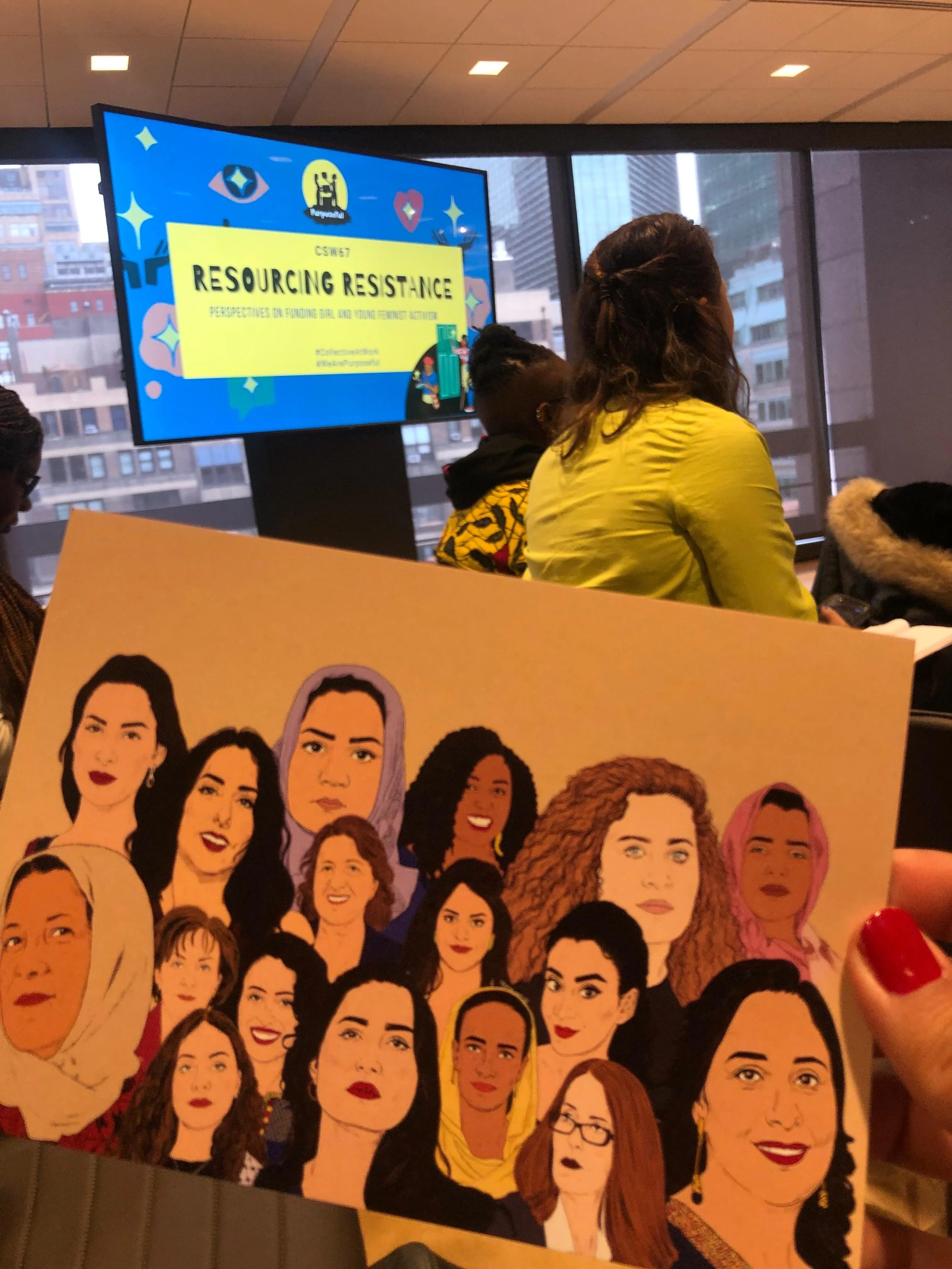

Photo: Alia Youssef

At just 23-years old, Ayat co-founded of the Libyan Youth Movement ShababLibya, documenting the uprising and difficult transition that followed in Libya. An activist and researcher on a range of Libya-related topics, particularly the youth movement and women's rights, Ayat reflects on her experience with Karama.

I was first introduced to Karama in 2011, in the aftermath of the Arab Spring’s Libyan uprising, that led to the fall of the former regime.

Harnessing Social Media to Support Activists

In 2011, I co-founded an online social media platform that set out to cover the Arab Spring as it unfolded in Libya. After the uprisings that took place in Tunisia and in Egypt, we saw that there was this really strategic use of social media, used to break through the censors, and empowered individuals to share their experiences with the world. We continue to see parallels of that until today around the world.

At the time, Libya and its population were controlled completely by the Qaddafi regime, including the media, the image that represented Libya to the outside world, and the regime’s own public image.

Having myself been situated in diaspora – I grew up in Canada, but was born in Libya – I was able to witness what was happening in Egypt and in Tunisia through the use of citizen journalists, as they called them at the time, essentially tweeting updates of their local contexts live.

We wanted to replicate that in Libya because we knew that it would be more difficult for those on the ground to share what was happening, due to the regime's control on the information, technology, internet, and the omnipresent threat of violent repression.

That's not to say that wasn't happening already. We sought to amplify voices on the ground, and we did so by connecting with sources that started with our relatives, and grew to include anyone that was willing to speak out.

From there, we launched ShababLibya, a social media campaign to contest the regime's dominant narrative. We started on Twitter, used social media tools on Facebook, as well as Skype and Messenger to connect with sources.

“We launched ShababLibya, a social media campaign to contest the regime's dominant narrative.”

The Libyan Youth Movement:

Fighting for their Country’s Future

The launch of ShababLibya felt very much something that my co-founder and I were fated to end up doing. We had bonded over living in diaspora, and our hopes to return to Libya, to contribute to Libyan society, and to maybe even go back and live here, and – quote-unquote – ‘wanted to see the end of the regime’. We felt we had been kept from Libya, and weren’t able to fully be a part of Libya, because of the regime.

When we met, we had joked that if we needed to do something for Libya one day, we should work together. Lo and behold, things kicked off in Tunis, we were still in touch, and we thought, okay, maybe this is something that we could do. But everything happened very quickly. We didn't think all that hard, we just launched into it.

Tunisia and Egypt had shown us proof of concept. We knew that social media was a thing that was striking a chord with people. We watched the Tahrir Square live feed on CNN, and so we started with the two of us, and our network grew naturally through other friends that we had that we knew could be interested.

We reached out to friends and family, in diaspora. When the uprising started, we never had confirmation if things were actually going to kick off on February 17th [the planned ‘Day of Rage’ for mass protests against the regime] or not. In fact, they did prematurely on the 15th; mothers who lost sons in the Abu Salim massacre were having their regular protests only for their lawyer to be arrested. That was the point of no return. The people were going to come out and protest. The Arab Spring was going to reach Libya.

Once things kicked off, Facebook became the medium where people started connecting and sharing. Because the situation had turned so violent so quickly, people wanted to raise awareness and spotlight what was happening.This was a matter of life and death. And so, through word of mouth, we were able to connect to sources, and we sought out sources where things were taking place.

At the same time, there was a live stream started from Benghazi in front of the courthouse by Mohamedd Nabbous. He demonstrated to us how to report on Libya. He was this person who was on the ground, who loved his city, loved his country, and knew that he needed the world to witness what was happening. [Nabbous was shot and killed by a sniper in March 2011 while covering protests in Benghazi. He was 28 years old.]

It was several networks, with people doing what they could organically. Everybody has their story with Libya. From the diaspora, there's a diversity of communities, and some people knew each other growing up, and others not so much, and connected during the revolution. I was definitely one of the latter. I didn't have a huge Libyan community growing up, and online was really the way that I was able to connect and participate.

Broadcasting Local Voices to the World

Filling the Information Gap

The platform ended up growing into a 24-hour newsfeed. Because of the nature of the events that unfolded – regime forces opened fire on protesters– it was imperative to continue to shed light on what was happening. Ultimately, those efforts and the efforts of many others, advocating for what we had set out to do – democracy, human rights, and a chance at electing our own leaders – resulted in the UN Security Council passing a resolution to implement a no-fly zone over the Libyan airspace. I believe that saved thousands of lives, and changed the trajectory of the uprising. We saw how things played out differently in other countries at the time, including Syria, that was asking for the same thing.

When it came to media coverage and knowledge of Libya, there was this huge void. Certainly, the Libyan media was controlled, and we saw the journalists that did end up making it to Tripoli before the fall of the regime were essentially relegated to a hotel. They had minders, they couldn't leave, and had to rely on people speaking to them anonymously from various parts of the conflict.

Then in eastern Libya, because the protests turned to civil war and was able to topple the regime so early on, journalists were literally driving through the Egyptian border. They were just coming through, and it was really open. Now we know there are positives and negatives of something like that happening, and we aligned a lot with what even the international media reported and wanted to report about Libya at the time.

The impact of attention and media and narrative is undeniable, and we continue to see that today. It was this really brief moment of almost being unfiltered. It was very much reflective of the will of the people. But at the same time, I will say we were lucky, because it ended up aligning with what the international community felt, because the regime had become so unpopular, and essentially such a nuisance. I hate to say that, because there's this kind of counter-narrative that ‘the Western powers just wanted to get rid of Qaddafi, and you gave them that opportunity.’

Was there overlap? Maybe. I am sure there will be studies about this for decades, about what had happened and who came in through those open borders. There were a lot of journalists, but probably a lot of other nefarious actors, a lot of those that essentially pillaged what that they could pillage while the chaos was happening. There were a lot of documents and files that disappeared, were destroyed, or had gone missing, and that just happens because it was chaos.

On the flip side of that, as ShababLibya, we had sources on the ground, but we were fully virtual, and we were consuming the media reporting on Libya. The reason we ended up continuing our efforts was that we constantly felt that Libya was misunderstood. It was very poorly understood by the West. There wasn't this essential ‘we know Libya's in North Africa and that’ etc. No, Libya was Qaddafi and it was desert, and that was that.

We felt we had to constantly play a role of providing important context to what was happening, that nuance, and noting that ‘no, this event is significant for this reason. This population or these people are asking for this because of this, XYZ.’ There was that propaganda element that we had to counter and it ended up meaning that we persisted for so long, and we continued to tweet and report, because we knew that so many things wouldn't get picked up by the media.

The media only had a very short attention span, but we wanted things to go on record, so we would talk to different people and keep up with a lot of the conflict that we knew was beyond the attention span of mainstream media.

Return to a Libya

in Transition

It was in October 2011 that I connected with Karama, for the Libyan launch of the Libyan Women's Platform for Peace which followed their initial launch in Cairo. I was in London, in September to start grad school, and I connected with some Libyans there. A Libyan writer I met and shared my story with told me about Zahra’ Langi, that she had ust launched this platform in Cairo, and suggested that I connect with her.

I did so and Zahra and immediately she told me to come to the launch in Tripoli. It was significant as it was my first trip to Libya since 2006, I didn’t even have my own Libyan passport. As I’d approached adolescence, I think my parents became more sensitive about political issues and wanted to shield me from getting in trouble if I were to go back. That was one of the reasons I’d had such a long absence from the country of my birth.

Meeting the Women Who Made History

Going back to a liberated Libya post-Qaddafi was my first introduction to Karama. I attended their conference and was introduced to an amazing group of civil society activists. It cannot be overstated, these were THE women who were a huge part of what Libyans had achieved in 2011. Their courage and bravery were a source of great inspiration, not just for myself, but everybody watching around the world.

It was a very formative experience for me and my path. I was able to share my story with them, and it was an opportunity I don't think I would have been afforded in another space. It was such a unique moment to talk to women activists from across the country, introduce myself, and hear about all of the various ways that they have contributed to the uprising. All of their expertise and know-how that they bring to the table; these were lawyers, professors, doctors, they were ministers in the transitional government at the time, and they were people that I had followed online, throughout the uprising, or that I had heard of.

Having that space to meet with them was very valuable, and then meeting the young women that were also in attendance. Most everyone that I met there I am basically still connected to today, 15 years later, so it was such an important moment for me. When the uprising is unfolding, everybody's somewhat in their lane, and they're working on their day-to-day reality, and you're doing what you’re doing, whether that’s just pushing out information, or you're, organizing campaigns, or whatever the arena that you operate in looks like. There isn't that much time to connect with people that are hustling like you in their lane. You might know of each other, but there isn't that opportunity to really come together. That's what that initial meeting was really successful in doing.

It ended up being a place where a lot of us met, and there are several who are no longer with us. I met the late Salwa Bugaighis, the late Siham Sergiwa, the Minister of Health at the time Fatma Hamroush, Dr. Najat Kikhia–women who were inspirations for us, women we viewed as holding the lantern for us to move forward, and we would follow them anywhere. It was a critical moment.

Contributing to a Changing Media Environment

In 2014 it was still quite early days. Some of our members from ShababLibya had moved to Benghazi, and so we were trying to build a base. I think we had registered ourselves as an NGO, and we were working with Libyan university students on activities like debate skills and Model UN, and then the reporting on Libya had never ended. We were still maintaining our online feed of what was happening, our concerns, but also highlighting good things that were happening in the aftermath of the fall of the regime. I had finished my studies in the UK, and I had moved back to Canada, and I was still living news cycle to news cycle. Any time one of these things would happen, Libya would come back into the news frame, it would be as if we started from zero. There wasn't institutional knowledge that journalists were building on. It was the same tropes, and so they would be asking ‘can anybody talk about this?’ Or we felt like we needed to report on Twitter, and then we would get asked by the media, ‘can you shed more light on it?’ And we would feel compelled to do so because there wasn't a viable alternative, at least for us.

I was committed to trying to have facts be involved, or context or nuance. I was still connected with the civil society on the ground.. We had started a platform called Libyan Youth Voices, where we published articles from young people's perspectives, on whatever they wanted to write about. A lot of it was the politics that was happening: the transitional governments, the mandates that they were trying to pass. There was a lot of discussion about that, namely the political isolation law that was passed and meant that anybody that had any experience under the regime was out. The direction the transitional government(s) took after passing that law, in my opinion, ended the brief democratic experiment that took place in Libya.

Up until the last days, we were talking to Tawfiq Ben Saud, we were interviewing him for an article. I wasn't on the ground, but I was still trying to continue to cultivate a space online for talking about Libya, and I was very much passionate about that. [Tawfiq Ben Saud was a radio presenter, journalist and activist. After receiving numerous threats, he and his colleague Sami Al-Kawafi were shot and killed in Benghazi in September 2014. Tawfiq was 18 years old.]

Learning to Navigate Media and Politics

I had started ShababLibya when I was 23. In some ways, some people would say that's mature, but for me, I can attest that I knew very little about the world at the time. I was very earnest. I think I was naive, and very ‘mask off’ - I said what I thought. I may not have been strategic, I was trying to be ‘oh, I'm gonna try to get my point across regardless.’ I just stuck to my message. I didn't necessarily massage it, but I was more than willing and capable in terms of doing hand-holding.

I had a lot of journalists approaching me - they maybe have never worked on Libya before, and I would be like, okay, here's the lay of the land, here are some contacts that I think you should get in touch with, here's some articles you could read. It was a lot of doing some of that groundwork. I did that for Al Jazeera English a lot, and a lot of other platforms.

Al Jazeera English had more interest in giving longer segments to Libya. There was a show geared to young people called The Stream, and they would produce a 45-minute show on Libya. They would interview 3-4 people, and someone had nominated me as one of their guests one time, and then it turned into me offering to help, 'if you want to talk about Libya, I don't mind, please feel free to approach me if you want recommendations or whatever.’ So for years, I was basically behind the scenes helping with their work. I don't think anybody acknowledged that that was happening, but they would say, ‘okay, we're doing Libya, can we call Ayat and see what she's thinking?’ And I would be like, ‘okay, this is who you should talk to, I don't think this framing works, I think this is more accurate,’ and again, every media platform has an angle, and has an agenda, and has something they're trying to get out of it, and I think that came to a head in 2015, 2016, 2017 with the war in Benghazi that ended up taking over. I think that's when I clocked it for real, because now what I was saying and what I was writing meant that I was relegated to one side of the conflict or another. And I did see the consequences of that.

The Cost of Speaking Out

One year, I think 2013, 2014, I was in DC about 5-6 times. I was invited to come, to speak, to be on platforms, to join panels, and then I wrote an article that used language that DC wasn't happy with, and I was never invited back. I don't regret it, but it became a wake-up call for me.I knew this, I knew how powerful the narrative and the medium was, but the consequence? Being actively silenced or isolated if you didn’t fall in line. We continue to see this strategy play out. So there's mainstream media, but then there's also what's being written, by, policy types, and how that writing is influencing decision-making in DC, at the UN, in Geneva. That's also like a front, a war zone, a war of words.

It was very much clear with the agendas, and if you follow the money, you know exactly who's setting it. That, combined with what was happening in the uprising, the drastic toll that women and young people have paid for taking on these risks, and, the reality, for me, personally, led to major burnout. There's a toll that everyone pays when they're working on these issues or working in this space. I wouldn't have known to avoid it, because I wasn't familiar. Now we talk about being on your phone too much, or being online too much, or being impacted by [volume of work], now we can talk about burnout in the workspace, and how it's something that you want to avoid. But there was a culmination of all those things that led to that for me, personally in my journey.

Social Media: From Empowerment to Manipulation

There could be many moments over time that demonstrated the potential of social networks, but I remember the first one was the Green Revolution of Iran in 2009. This was one of the first demonstrations of using Facebook and social media to mobilize and bring people together.

The Arab Spring is then this huge moment. We demonstrated how powerful it was, but then those that control those tools were these companies. Unfortunately, it is such a space that is unregulated, and maybe it is now more, but we exist in a capitalist system, we exist in a patriarchy, there's these neoliberal ideologies that drive things, and so the moral, ethical, good-bad elements of things aren’t at the forefront.

We saw it undergo modification at the behest of these companies, and then we saw the 2016 election, and the result of that in the US, that instead of it being a tool that would crowdsource people's sentiments, it became skewed to this negative misinformation machine. COVID as well was a big moment for technology at the time. The companies play a huge role, and unfortunately, at the end of the day, people who are most marginalized, or ‘oppressed’, or maybe belong to the identities that are least powerful are the ones that are the most vulnerable in these moments.

Now, we have this tool that was used to empower people and is now being used to monitor them, to influence them, to incriminate them, to intimidate them, so I think we couldn't now reproduce what happened then. Gaza is a testament to that, but it's also a challenge to that, because they have been able to do a lot. They have been able to raise awareness, probably more than has ever been, on the issue of the occupation and the apartheid. I'm glad that they're challenging us, so that we're not completely cynical and completely hopeless, because they continue to demonstrate that there is still power in people. And most recently, the election of Mayor Zohran Mamdani in New York, a social democrat, a young Muslim man, was elected with the highest voter turnout in over half a century. There continue to be glimmers of hope when people organize.

The Weight of Words

As with many words in communication, in media, things become loaded, and so ‘Arab Spring’ bears an implication. Now there’s a shadow around it, ‘Oh, it wasn't really that spring, it was the Arab winter, followed the Arab Spring,’ and also people contest the word Arab, for sure, because it oversimplifies the diversity of the various identities that exist in North Africa and Middle East.

Existing in the West, I think it delivers some meaning, Arab Spring, about a moment in time. But I know that the average person couldn't tell you what happened during the Arab Spring, couldn't tell you what countries participated, what was going on. But that's normal, because we still have a lot of frustration two years after genocide in Gaza, where you probably could survey a lot of people on the street, and they wouldn't be able to accurately tell you what is going on, or what is happening, or how they feel.

There's this aversion to news from our region, unfortunately. People are turned off in general from the history of a lot of the interventions and the military operations that have gone on since September 11th, and probably there was a whole other flavor of things before 9/11 that were cast against us anyway.

That's also one of the reasons why there's so many words and terminology that I use. For instance, I don't say the ‘Libyan Revolution’. I don't think revolution is an accurate depiction of what happened. It's not as if we were able to overthrow a regime and we put in something else. The revolution was not complete. So I use the word ‘uprising’ because I feel like that's a more accurate depiction of what had taken place.

For me, this issue is painful in the way that the scandals that we have had to endure from Western politics and their attention span, what the word ‘Benghazi’ became, for instance. Maybe less so now, but you couldn't look up the word Benghazi or say Benghazi without someone thinking you're talking about Hillary Clinton and a Republican-Democratic scandal that they have relegated it to.

It’s very damaging to see words being misconstrued, and it emphasizes further the need to constantly have a Libyan-centered, Libyan-authored, perspective on things. But the flip side of it is that the power of media is what makes it just as dangerous, and so you have people constantly taking risks to be in that space. That's what ended up unfolding in Libya in the early years after the uprising. Now, this amazing tool or this amazing moment happened, where people came together is now being targeted. And if, I dare say, if there was a new regime in place, it would have been criminalized or regulated. Any source of power other than whatever is ruling a country is going to be deemed threatening, unless you really have institutions and a system in place that respects democracy and human rights and freedom of speech. We are not there.

Growing with Karama

Image: UN Photo/Loey Felipe

Karama’s presence has come through many moments over the last 14 years. I can't even imagine. I can't believe that we're 15 years on. I met Karama in year one of the uprising, the beginning of my journey with this space, and I was impacted by the demonstration of this collective moment that we had. It was transnational, Hibaaq coming from this regional network, and has connected us together. This fierce Somali woman comes and cares about Libya, cares about women from the region, and brings this wisdom. Definitely the element of just gaining Hibaaq and Karama as mentors has been [so important].

I consider myself very fortunate to have been able to be in the network, and there were many years where I wasn't connected because of fallout post-uprising. The intimidation tactics and the targeting of activists, and how it became quite dangerous to be in Libya. Then, there was this moment where, after the uprising took place, now we're free, we can get offline and go to the ground. I wasn't able to relocate and be in Libya. There was a lot of decisions that were made that were very quick, where we want to talk to activists on the ground, we want to work with people that are working in Libya, and and then as things became a little bit more difficult on the ground, power and security was centered in Tripoli, then it became, ‘oh, we want to talk to activists in Tripoli, because that's where all the NGOs had relocated,’ and it was a difficult space for me – as someone who was working as a youth activist at the time – to navigate. I was constantly being relegated, [I would hear] ‘we don't need you any more. You live in the diaspora, we need Libyans on the ground.’

I continued to follow and be connected with Zahra’, Karama’s partner in Libya, and they were able to afford us opportunities to engage. Just watching them continue to persevere in Libya, and constantly mitigate the threats, and then still continue to be a presence, even after the assassination of Salwa [Bughaighis], and Zahra having no option but to continue operations from exile effectively.

These were examples of how we could continue to work even if the conflict had to push us out. And then, when I was able to reconnect with Karama again in New York at CSW in 2019, and it was like I never left. I was welcomed with open arms. That's also a huge factor in Karama, that they are such an open space that you feel included, that there is this, intergenerational, respect for dialogue. I feel like I could call and ask for advice on anything, and the time would be made to speak, and the support would be there.

Opening Doors and Building Connections

I was introduced to a generation of women activists from the region, and now, all of a sudden, I was plugged in almost overnight. It has been very meaningful. They connected me with other young women from across the region, we attended Women Deliver together in Vancouver. I was able to attend the African Women Leaders Forum at Yale alongside prestigious African leaders. Had it not been for Karama nominating me for something like that, I would never have nominated myself. Even the support and the encouragement and the vision that Karama has for its members is something that has made tangible change, result, reality for me.

I was introduced to those who work in the space for making grants for girls' initiatives, and that led me into working with the Girls Resistance Stories Project, and Karama was not only important in connecting me with the project and led to me becoming the story curator for the MENA region, but also facilitated introductions to storytellers so we could collect their stories.

The collaboration, the support, the solidarity, and care is something that has been really meaningful for me in my life. Karama is a safe space, but also a space to strategize, a space for action, and it's just very energizing as well.

Adapting and responding Through Crisis

Karama has proven itself to constantly meet the occasion, where it is, and constantly come up against challenges and find really creative ways to deal with it. With COVID, everybody was relegated to their homes, and we went from a place where, right before COVID, we were meeting regularly, and there was a lot of momentum, a lot of excitement around coming together and building these regional movements. There was also the work with adolescent girls, empowering young women across the region and building their networks. And then all of a sudden, everything came to a halt.

I'm sure it was very difficult for everybody to face that reality, in their own way. There is a lot to be said about the issue of COVID itself and the injustice that ensued around the whole world about who was able to access healthcare or aid or how people are impacted, unequally and unjustly. But Karama didn't really miss a beat. Their response was, ‘okay, we're gonna do this online, and we're going to come together and support each other using Zoom,’ and we started these virtual series, a multitude of them. There was the intergenerational knowledge-sharing that we kind of got to hear from members that we always knew were in Karama, but maybe had not had a chance to talk or hear from, one-on-one.

There was the dialogue series that we did with feminist heroes. We were able to have time with Hanan Ashrawi to talk about the Palestinian liberation movement, and we also had a session with Jane Fonda. We were able to have these conversations in this space and these moments that you can't get anywhere else.

Again, any moment where things are happening, Karama is always thoughtful and responsive. We've witnessed that with what's happening in Gaza more recently, but then also in Sudan, and in Yemen. Karama is alive, it's this living entity that's going to be responsive, that's constantly strategic, and meaningful. The inclusivity in Karama extends to their decision-making: there is space for our input, our ideas, we are valued. Karama has shaped my identity as a woman, as a feminist, as an ally and activist simply by reflecting those values in everything they do.

Looking Forward

Thank you Karama for everything you have done and continue to do. Now, if I could just get a chance to spend an extended period-either one-on-one or in a large Karama gathering - focused on Hibaaq, I would love for us to capture her biography, life story and wisdom.I believe it would be remarkable and must be shared.

I don't know if something like this network exists in the region or elsewhere. I've had a very positive relationship with Karama. We have some real gems, and it's been for me a positive and inspiring and empowering engagement over the years. I hope to continue to be part of the network, and I hope to be able to contribute in ways. I'm very proud to, to be affiliated, to be associated, and to be included in such an esteemed network. There's been lots of learning opportunities and capacity building and just awareness.

Just being part of the network gives you so much. You don't have to do much to really benefit, but then there's also so much potential if you would like to engage more. I feel like it takes you where you're at, and I really appreciate that.