Zahra’ Langhi

Even before the establishment of the Libyan Women’s Platform for Peace, even before the fall of the regime of Gaddafi, my journey with Karama started in 2011. We were coordinating the first meeting for Libyan women that took place during the War of Liberation.

In that meeting, it is now 14 years ago, in the first week of October, Karama coordinated a meeting of women from across Libya, from different walks of life. It was there that we established the movement, the Libyan Women's Platform for Peace. So the Karama is the mother group of LWPP.

We brought together 33 women for the first meeting ever for Libyan women from across the country: from the East, from the South, and the West.

We made sure that there was criteria for selection, ensuring that it included intergenerational representation. We had women like Najat Kikhia, representing the Scout movement, who was the first woman elected for the local council, from an older generation. She is the sister of the late Mansour Kikhia [the founder of the Libyan Human Rights Association]. There was Naima Jibril, who was the first woman judge in Libya. We had a younger generation, like Waf Yasif al-Nasser, who later on became the first assistant foreign minister. When she first started with us, she was only 22 years old.

Hannah El-Hebshi, known as Numidia, who took part in supporting the freedom fighters, militarily, was also a participant. With her, there were also a couple of young field activists who were supportive of the Freedom Fighters movement. We also had women academics whose background was primarily on preserving the institutional memory of the women's movement in Libya.

It really was quite diverse. People from civil society, from the younger generation who worked in the field, along with supporting the Freedom Fighters movement, judges and lawyers, like Amal Bugaighis and Salwa Bugaighis - two women who were the first to be present in front of the courthouse in Benghazi in February 2011 calling for the fall of the regime.

The meeting took in a broad sweep of representation, in terms of geographical, cultural background.

Bringing Together Leaders From Across Libya

It is in that meeting that we strategized together, along with our international partners– Karama and through them the regional and international actors that were present at that meeting–how to chart the way forward for an inclusive transition in Libya, a transition that would center women’s equal, full, and safe participation.

Those who came to the meeting were already leaders in their own right. They were already established with their diverse backgrounds. They were aware that women would pay the price in the transition, after the fall of the regime, and were feeling that they were getting more and more excluded.

There were these concerns in these meetings and that is why, when we brought all of them together, there was such consensus around inclusivity in decision making. Though some of them were from the East, which was already liberated at that time, the West was not liberated at that point. That is why we were keen to have this meeting, not in Benghazi, but outside of the country.

The first meeting after the fall of Gaddafi a month later, took place in Tripoli, and then from Tripoli, we went to Benghazi. So we were keen to always make the balances.

Creating a Movement and Securing Women’s Participation

We started to build a movement across Libya to focus on how to ensure inclusivity and women’s political participation. We organized workshops, meetings, consultations with policy makers, with political leaders, with youth activists, with women human rights defenders, with civil society groups, media, security actors.

LWPP worked on a draft for an inclusive electoral law, which was, eventually, adopted by the National Transitional Council, the executive and legislative body in the first transitional period.

That law made it possible for the very first time in 52 years for Libyan women to secure 16.5 per cent minimum of the seats of the legislative body. That minimum has kept throughout Libya's transition, right until the present day. That quota for women's participation is thanks to our efforts and, basically, to the support we had from Karama.

It is not easy to bring and to unite the forces even within the women's movement. Doing that was one of the major successes of the LWPP, thanks to the support of Karama. The whole idea of the platform for peace–and back then, when we said peace, no one was talking about peace–people were talking about democracy, change. But from the very first day, we said we will call this movement ‘peace’. We wanted to make sure that we unify and unite the forces towards an inclusive transition where there is gender equality, there is an equal, full, meaningful participation of women.

Building Trust Across Sectors

Even at times it was difficult to maintain it, but because of our successes we were able to maintain it as a collective. From the very first year, in securing the electoral quota in the first electoral laws when everyone was doubtful that we would be able to do so. People from different backgrounds trusted us, including senior political officials, senior security officials. Later on, we started to work even across the security sector with militias, with representatives from the former security sector, with the legislative, executive bodies, local mediators, tribal sheikhs.

We were able to engage with these actors, they trusted us, they knew that we were backed, we had the support, and mainly it was possible through Karama creating platforms for us to engage with international actors and amplify the local voices and send their messages. We were able to influence and to apply pressure on those officials on the ground. It is through that whole process that we gained the trust of diverse sectors from Libyan society, mainly women, representatives of different backgrounds, to unify their forces and to create a strong movement in Libya.

The Karama Network Made a Difference

We have always found solace and support in our affiliation with the Karama Network, whether through the vital alliance that fortified our strategies and provided us with resources, connected us with experts, policy makers, donors, media outlets. That is the main support we have had from Karama.

Through the network of Karama, we engaged in profound exchanges with colleagues from Syria, Sudan, Iraq, Palestine, Yemen. Sharing, knowledge, best practices, lessons learned from our collective struggles. This continues right up until now, as the LWPP along with two other organizations from South Sudan and Palestine benefited from Karama's support through its grant from Norad.

*The Libyan Political Dialogue Forum or LPDF was a political track established by the United Nations. The LPDF produced a roadmap to presidential and parliamentary elections that was endorsed by Security Council resolutions 2510, 2570, 2571. It began with selecting an interim Government of National Unity (GNU), followed by national elections – a sequence intended to intertwine state-building and democracy.

Women Leaders Shaping the Peace Process

Karama has empowered our national, women's organizations and movements, making it possible to develop effective strategies for the implementation, later on for even the Libyan peace process. Women were leading and participating meaningfully when we came to the last peace process that we had in the Libyan Political Dialogue Forum* where, unprecedentedly, Libya had 22 per cent of women participating in a Track 1 process.

Out of those women participating in the Libyan Political Dialogue Forum, a good proportion were from the LWPP. Even now in the advisory committee, we have 30 per cent women’s representation. Half of those women are from the LWPP, supported by the Karama network

To be in this position, to be working effectively and sustainably, is not something we should underestimate.

From the National to the Local

In the very first 6 months of the revolution, during the War of Liberation, it was a remarkable time for civil society. Perhaps more than 200 civil society organizations were established in the East. Later on, after the liberation, around 1,000 were established.

There was a very vibrant civil society in early 2011, in 2012, and even 2013, a very active time for the work and the advocacy of civil society. LWPP first gained prominence when our first campaign on the inclusive electoral law was successful. That made everyone look at us and take us more seriously, even among those senior officials or political parties.

Later on, our work changed to what I will call it our localized, bottom-up approach, working from the local priorities and needs of the communities.

At that time, our main theme was reforming the security sector. Immediately after the elections, and after what we have seen was a time of political polarization, and domination. In 2013 political assassinations had already started. Our attention was on and initiatives were focused on local dialogues or consultations on demobilization disarmament reintegration (DDR), on reforming the security sector (SSR), and not on any issues related only on women's representation and participation.

For us, from day one, we were never engaged in siloed narratives.

That is how we gained the trust and credibility of local communities, as we have engaged everyone, even if the funding, in many cases, came under women, peace and security (WPS). We never said, ‘okay, let’s bring you together and we will teach you what this resolution says.’ No, we start from the local priorities and needs, and then we make reference to the Security Council resolutions or the WPS agenda.

That is how we localize the agenda. We start from the local needs and priorities, which back then were militarization, ending impunity, reforming the security sector, dealing with local reconciliation. And women were leading these efforts, both at the local and national levels.

Many talk about localization, but have no idea what localization means. Localizing is not about bringing something foreign that you parachute into a local context, and tell people they need to accommodate it. No, you start from the local needs, you listen to them very carefully, you want to watch carefully and absorb the local context with its sensitivities and do it with humility.

Take the unfortunate case of women, peace and security national action plan (NAP) in Libya. There you had the signing of an MoU between UN Women and the Ministry of Women's Affairs to develop a NAP to implement UNSCR 1325. There was a complete lack of a sensitive approach, as well as not having good two-way communications. As we have seen later on, people did not know the substance of what was actually agreed. People thought that Libya was signing on to a convention akin to CEDAW. So during and even after the event, there were no communications. Even up to this moment, people do not understand and never understood what happened.

Rebuilding Community With Security

Even later on in 2014, when our colleagues like Salwa [Bugaighis], Tawfik [Bensaud], Fariha al Burqawi were assassinated, we had to think and to reframe our entire strategy. That is something that I am always grateful to Karama for. Karama has always been flexible with us, and understands the importance of political and cultural sensitivity, and how we need to always frame our messaging and communications.

After 2014, there was an attack on civil society not only by the militias, or the de facto authorities, or the warlords, but there was even a kind of resentment from local communities. By 2017, 2018 there was mistrust, especially within local communities towards civil society organizations that focus on human rights. People at that time were fed up of anything related to democracy. They just wanted security.

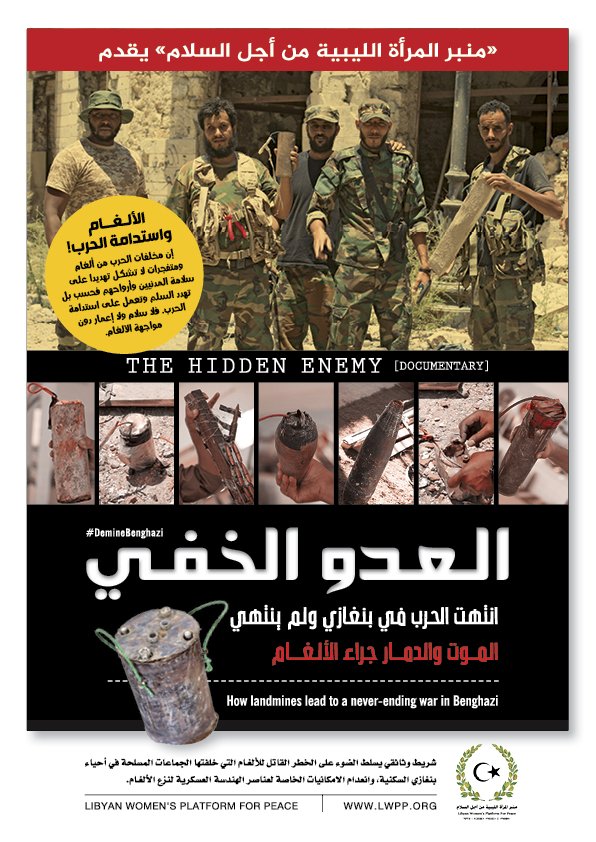

At that time, Karama had secured funding from the Netherlands specifically under a human rights program. Our work focused on economic and social rights, not the focus on civil and political rights, specifically we focused on the need to remove landmines. At that point, mines were a big issue for local communities, especially in Benghazi.

Campaigning on de-mining was an entry point to not only engage with local communities again, and to rebrand ourselves, making us more relevant to their needs and to tell them that this is a human rights issue that is relevant and important to them. But it was also an entry point to the local authorities. We re-established the trust relationship with the de facto authorities or the National Army.

That campaign produced documentaries on the daily threat of mines, and the Chief of Staff took it and screened it during his visit to Moscow, calling for tools to carry out the process of de-mining. Through our work, they felt that civil society or human rights organizations do not have to be necessarily antagonistic towards authorities. But we can build trust relationships in common areas when we are both focusing on people's needs and priorities.

Connecting to Religious Leaders and Scholars

In the same period, and also with the support of Karama, we worked on reforming the religious narrative, and how to ensure that we are not allowing ourselves to be pigeon holed by our community.

Both in Libya and in the region, we managed to establish very important and strategic relationships and partnerships with Al Azhar university, the region’s pre-eminent Islamic learning institution. With that strong relationship with Al Azhar as a foundation, we were able to access and invite traditional, religious Ulama (scholars of Islamic doctrine and law) from Libya, to come and take a training session on CEDAW - but wearing the hat of being partners of Al-Azhar.

So we managed to do all of that, and do it again in Zeytuna university in Tunis, and leverage all these networks for advancing the WPS agenda, and even the CEDAW. These I see, as among the success stories we have been able to achieve through our close partnership with Karama.

I always say this is the difference between the top-down approach and the bottom-up approach, the difference between having a conflict-sensitive approach or an approach that you just copy-paste from somewhere else, with no understanding of the local context.

That is the importance of humility, courage, and transparency. Understanding the local, sensitivities, and the context, and respecting it. That failure caused great losses, for UN Women’s work in Libya, for activists who work on WPS agenda, some of whom were threatened and had to flee the country. Even up to this moment, nobody can dare talk about working on a NAP. UN Woman now works only on economic empowerment in Libya.

“Many talk about localization, but have no idea what localization means”

Local Women Mediators as Peacebuilders

We are currently working on a project with Karama to establish a network of women mediators.

Around 7 years ago, I conducted a field study on local women's mediators in Libya. It developed from a sense of frustration I have felt myself as a national mediator. I was faced with many obstacles, but I have seen local mediators who are invisible, not seen, who are able to make more successes. The interesting thing is that these local, traditional women mediators are not even aware of the WPS agenda.

They know nothing about 1325 or the related resolutions. At the beginning, some of them were not aware that they were doing mediation. They were sometimes mothers of abductees, mothers of prisoners where they have managed to successfully agree to exchange of prisoners, to open roads, checkpoints. Such examples are not only found in Libya. I have seen it in Yemen, in Syria.

It is this kind of local women's mediation that inspires me. First of all, it is very much embedded in and grounded in the local culture. We need to refute the narrative that women's political participation and participation in peace and mediation is a foreign intervention. We need always to say we are doing this because this comes from your local culture, and it happens to be also supported in global norms, not the other way around - ‘you have to do it because the Security Council has decided so-and-so.’ We should be focusing on and highlighting the stories of these women, many of whom we have been working with the last two years. We are working to galvanize them as a movement, and create this network of local women mediators.

A few years ago, we started this campaign on the stories of local women mediators. This year, we would be focusing and highlighting 25 stories from the local context. It is to amplify the voices of these women as well.

Karama Creates Regional and International Access for Influence

At the regional level, Karama creates for us that kind of platform where we can exchange with others, fellow leaders, civil society leaders from other countries in the region and internationally. We exchange with them knowledge, best practices, invaluable lessons learned from our collective struggles. On the horizontal level, we have learned together as women human rights defenders and civil society partners in the region. And at the vertical level, we bring the stories from the local national to the international level.

That is one of the major benefits of the Karama network. It has provided us with essential resources, support, and connected us with policy makers, donors, international actors, media outlets, at the international level, to amplify these voices and to highlight their stories so they are not invisible anymore.

That is really exemplified by the campaign Justice for Salwa. We took her case up to the United Nations Security Council. It was the first time that the murder of an individual non-governmental woman was mentioned in a Security Council briefing. When the Netherlands was a member of the council, they called for an open, transparent investigation that would be led by the ICC. And we as campaigners have gone as well to the ICC.

Justice for Salwa

With Karama we have done a lot in the case of Salwa. We even met with the UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, with the president of the General Assembly also, and we were advocating back then, we were talking about the protection of women human rights defenders in 2014. We were pushing for a resolution by the General Assembly, which was not possible, but back then, nobody was talking about protection of women human rights defenders, so I think we have done a lot together, even at the global level.

Reaching Across the Country, the Region and the Globe

We made Salwa’s cause an international cause, as well as a Libyan cause. Each year, we cover it from different perspectives - accountability, peace, democracy - and it is a global debate, not only a national debate, so we took it many steps further.

When we think of the strategic partnership that we have done with Al-Azhar, we then expanded that with Zaytuna, we worked in the Sahel, we worked in Maghreb, so it is not even Libyan. We created these networks that are still there.

Lately, Karama has been supporting a whole podcast about the meaningful participation of women in the peace process. This is shedding more light on the role of the advisory committee that I mentioned earlier. Karama has been a great support not only for LWPP, but for the various women's movements and organizations in Libya.

Through Karama’s support, whether it has been engaging us with donors, policy makers in the global north, through media outlets, it has amplified our voices and to lobby internationally. And not to forget, of course, the global campaign: Justice for Salwa is justice for all. I think this is one of the major successes we had working together as a national movement with a regional, international network like Karama, advocating for ending impunity, and calling for justice, not only for Salwa, but those who are victims of political violence, and calling for the protection of women human rights defenders.

Through the unwavering support of Karama, for 11 years, we have made the Justice for Salwa campaign sustained, advocating and continuing. Calling for the equal, full, meaningful, and safe participation of women.